“The period of time between 1958-1963 was marked by slow but steady efforts to build the financial base of Exceptional Foresters. The difficulties encountered and the slow pace of progress of those years stemmed from a desire to build the organization without the aid of government funding. To bring the dream of a community-financed care facility to fruition, the Board members and supporters of Exceptional Foresters, Inc. postponed accepting clients until enough privately raised capital had been accumulated. True to their principles, the Foresters preferred time and effort to the haste and hassle that often accompanies government aid.

By 1963, however, the Board and membership were becoming restive. A point had been reached where the Foresters would either have to fish or cut bait. Much time and effort had been expended in laying the groundwork for the organization and there was a growing sentiment to get at least a small part of the program underway. It was at this point that Exceptional Foresters found its first supervisor.

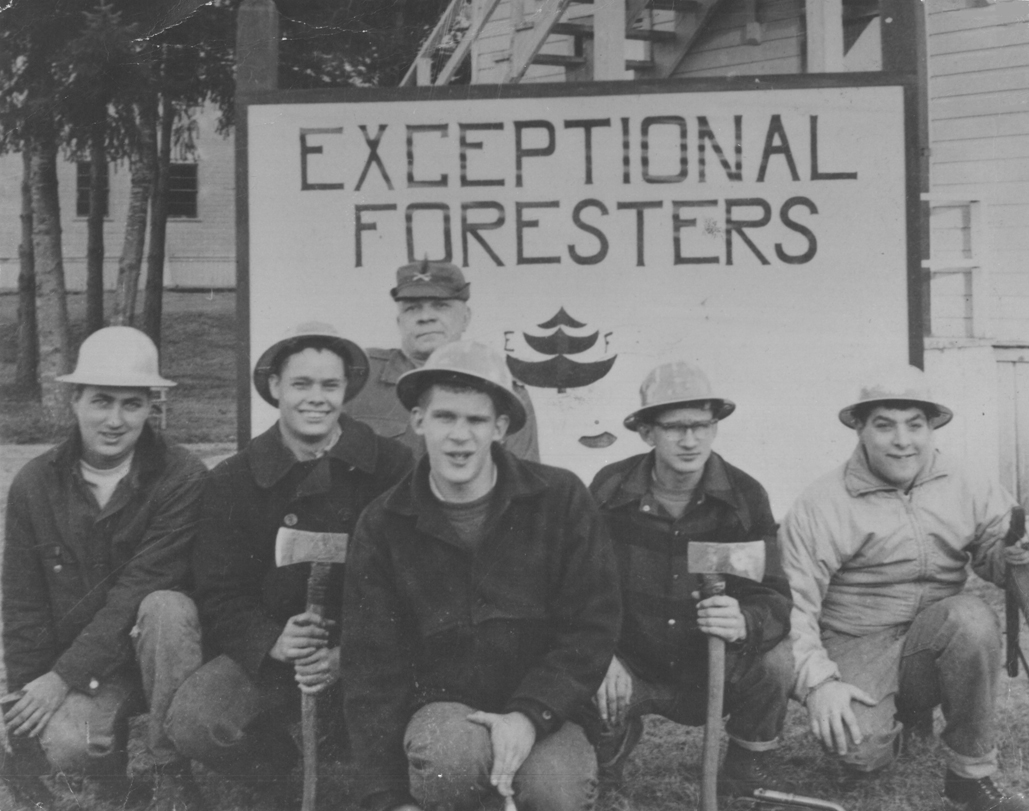

Al Wagner had been very active in the program and was strongly committed to its success. So, when it became obvious that something had to be done, he brought forward a generous proposal. Begin-fling in July, 1963, Wagner would request a one year leave of absence from his teaching profession at Rogers School and commence the first training program for clients of Exceptional Foresters, at no charge to the organization. During his sabbatical he would train five men in various work projects: sweeping lots, janitorial service, or working in the trees. The important point was that they would do something.

The first five Foresters were a productive lot and readily took to the chores offered by the program. The training, as such, was simple and unassuming, but in consequence, of a profound and immeasurable nature. The humble task of sweeping the dust and debris from the sidewalks of a small rural city represented nothing less than a revolution in the care of mentally handicapped people. Instead of segregation and isolation, the retarded individual was now involved in community life, filling a needed, albeit modest, role in society. Without the development of the Exceptional Forester concept of vocational training, it is difficult to imagine how the lives of these men could have grown beyond complete dependency. As a result of their training at Exceptional Foresters, two of the five original clients are now employed in the private sector. One of them works for the Simpson Timber Co. on its railroad crew and the other has worked for years in the Mason County Christmas tree industry. Both men are fully integrated into society, living useful productive lives.” This is Exceptional Foresters by James H. Lindley